ONE day in March 1968, a presidential helicopter swooped down on Corregidor shortly after the killing of young Muslim men being trained to infiltrate and destabilize Sabah. Officers and men belonging to the Army Special Forces leaped out of the aircraft and engaged in a clandestine cover-up mission to erase traces of a key historical event that has come to be known as the Jabidah massacre.

It was the spark that lit the Muslim rebellion, the Plaza Miranda of Mindanao. (Plaza Miranda, in the heart of Manila, was where the Liberal Party senatorial candidates opposed to then President Ferdinand Marcos were bombed in August 1971 while holding a political rally. Nearly a hundred, including the candidates, were wounded and nine were killed.) From then on, Muslim Mindanao was never the same again.

Corregidor was a forlorn, tadpole-shaped island guarding the mouth of Manila Bay. Its tail tapered off toward Cavite, and on the island stood ancient artillery, battle scarred fortifications and ruins, and a tunnel bombed during World War II. A small community lived in a pocket of the island, removed from the comings and goings.

When they landed, the teams of soldiers found burned bodies tied to trees, near the airstrip, on the island’s bottom side. The order from Army Chief Gen. Romeo Espino was to clean up the place and clear it of all debris. From afternoon till sunset, they collected charred flesh and bones and wrapped them in dark colored ponchos. They could not keep track of how many bodies there were. They also picked up bullet shells lying on the airstrip. The trainees had been shot dead before they were tied and burned.

It was a swift operation. What the participants remember most is the strong smell of death and decay. That night, these soldiers burned their clothes which had absorbed the stench. At the crack of dawn the next day, they loaded the ponchos in the helicopter and flew over Manila Bay. They tied heavy stones to the ponchos before dumping them all into the sea. The remains sank, weighted down by the stones. The soldiers made sure nothing floated to the surface.

At that time, under the iron hand and expansionist tendencies of President Ferdinand Marcos, the killings on Corregidor were never explained. If Marcos and his men were to be believed, they never happened. The expose on Jabidah, they said, was part of a grand plot by the opposition to discredit the Marcos regime; furthermore, Jibin Arula, a survivor of the massacre, was an agent planted by Malaysia after it had uncovered Jabidah’s purpose.

The Armed Forces top brass never ordered a search for missing persons, living and dead. No real investigation took place, except for a few Senate and Congressional hearings which yielded inconclusive findings. The young and intensely energetic opposition Senator Benigno Aquino Jr., using his deft journalistic skills, put some of the pieces of the Jabidah puzzle together, but the picture remained incomplete. Nevertheless, given the period’s secrecy and silence, Aquino’s was the most thorough investigation.

Eight officers and 16 enlisted men were court-martialed in 1968. All of them, however, were cleared in 1971. No qne was held accountable for the gruesome killings on Corregidor that forgotten day in March 1968.

Destination: Sabah

Inside the soldiers’ quarters in Camp Crame, bored young lieutenants watched another idle night go by. Fouryears of rigid training at the Philippine Military Academy (PMA) and now this, they grumbled to themselves: desk work, serving as aides to generals, writing speeches forthe top brass.

Itwas 1967. There was no big war insight. The Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) were the most experienced in Southeast Asia, having crushed the Huk insurgency. The economy was in good shape, hurtling way ahead of the rest in Southeast Asia, and, except for a tolerable number of .communist guerrillas, the rest of the populace seemed content with life.

Rolando Abadilla was a second lieutenant then, fresh out of the PMA (he graduated in 1965). Unlike his comrades, he was not bored. He had just joined a secret mission led by an officer with close linksto Marcos, Maj. Eduardo Martelino. Martelino was an articulate and dashing officer who easily earned the confidence ofhis bosses. He was a graduate of the Infantry School in Fort Benning in the United States, the Pilot School of the Philippine Air Force (PAF), and the Defense Information School of the US Armed Forces, the precursor of the psychological warfare school at Fort Bragg. The writer Nick Joaquin later described Martelino, when he showed up at the Congressional hearings on Oplan Merdeka in March and Apri11968, as a tanned, middle-aging adventurer with a lean face, mustache, world-weary eyes, domed forehead, and receding hairline. He had a husky voice and generally kept his cool.

That Abadilla was one of the initial recruits for the Jabidah operation did not surprise his PMA batch mates. Like Marcos, the young lieutenant came from Ilocos Norte. As soon as Marcos became president in 1965, his first move as commander in chief was to name fellow Ilocanos to lucrative posts in the armed forces. In Marcos’s time, to be an Ilocano in the military was to hold a sure ticket to a good command.

Marcos gave Martelino a broad picture of his plans regarding Sabah. The commando group that Martelino was to form had one mission: destabilize Sabah and take over the resource-rich island. Rather than wait it out in the corridors of international diplomacy, Marcos was keen on an adventurous and risky option, the swiftest and most direct means of claiming the Borneo island. After all, he and his men believed, Sabah rightfully belonged to the Philippines.

The planned invasion negated Marcos’s initial courtship of Malaysia in 1965, when he assumed the presidency. That year, he took the initiative of resuming talks with Malaysia and won in the process a significant concession: an anti- smuggling agreement which attempted to control the trade between Sabah and the Southern Philippines. The pact did not sit well with many Muslims, who felt that the agreement subordinated minority interests for national interests, according to Prof. Aruna Gorpinath of the University of Malaya. The border agreement, for one, ensured higher revenues for the government. It also implied that the Marcos government was willing to maintain its silence over the Sabah claim, which the previous Macapagal administration had pushed. Marcos apparently wanted to play a role in efforts at the time to form the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean).

Indeed, the wily president was confident that, given this legal cover, he could easily deny links with any illegal move against Sabah. The style was vintage Ferdinand Marcos. His loyalists in the military named the operation to invade Sabah “Project Merdeka” and the commando group “Jabidah.” Merdeka is Bahasa Melayu for freedom and Jabidah is the name of a stunningly beautiful woman in Muslim 1ore. Martelino was fond of women. In this case, Jabidah may have referred to Sabah, likened to a woman desired by the army he put together. In a way, it was an equivalent of Helen, “whose matchless beauty,” Aquino eloquently said in a Senate speech, “launched a thousand ships and laid the great Greek states to siege and waste.”

A recruitment spree

Each night that Abadilla retreated to his quarters in Camp Crame, which he shared with fellow PMAers, he would be cajoled into telling stories about his mission. He wouldn’t talk. But after one drink too many, he boasted about how he and his commanders were able to sneak into Sabah to deploy their own agents there. It was sometime 1967, the start of the infiltration process.

Recruitment was not limited to soldiers. Martelino also planned to form a medico-legal team to go with the troops during the invasion. In the summer of 1967, some officers of the Philippine Constabulary (PO were assigned to recruit medical students for the job, and they tapped as one source the Cebu Institute of Technology, which ran a medical school.

They (the PC officers) started asking us out for a friendly shoot,” one of the medical students then who was recruited to the team recalls. A Christian, he was born in Basilan and grew up there. That he was a Christian did not matter to his recruiters; what mattered was that he knew how to speak Tausug, the language of most of the prospective Muslim recruits. He would not name the PC officers who recruited him, however. One day while on a firing range in Cebu City, one of the PC officers began talking to the medical students about the Jabidah operation.” They never hid anything from me,the former student who is now a doctor says. “They said they needed my services for a medical team to be brought to Sabah once the invasion took place. I was thrilled. I had always wanted to be a soldier. And I was also convinced that Sabah was ours.

He was on his third year in medicine proper then. When the massacre took place, he was already in his last year in medical school. By that time, he had been enlisted into the medical team. “There was no promise of pay. But we were told that we would get a piece of land if the invasion succeeded. That was already okay with me,”he says. At least three medical students underwent training in Cebu for the operation. The training included physical exercises. After the massacre, they were called in to join a military team that conducted the mopping-up operations in Corregidor. They saw the lifeless bodies.

“They (the PC officers) checked the list of recruits. They wanted to make sure no one would survive. Then they found out that at least two had escaped, he says. One was Jibin Arula, the other was a recruit from Basilan. Since he was from Basilan, the doctor was assigned the task of silencing the other survivor, whom he refuses to name. He says he readily accomplished the job.

Infiltrating Sabah

About 17 men, mostly recruits from Sulu and Tawi- Tawi, entered Sabah as forest rangers, mailmen, police. Oil-rich, blessed with fertile soil, pleasant weather, and what at the time were lush forests, the disputed territory covers about 29,388 square miles. The Filipino agents blended into the island’s communities. Their main task was to use psychological warfare to indoctrinate and convince the large number of Filipinos residing in Sabah to secede from Malaysia and be a part of the Philippines. Part of their job was to organize communities which would support secession and be their allies when the invasion took place. They also needed to reconnoiter the area and study possible landing points for airplanes and docking sites for boats.

Martelino himself went to Sabah three times on secret missions as head of the Jabidah Forces, he would reveal in a newspaper interview on August 1, 1968. Thelanding points he used were Tambisan Point, lahad Datu, and Semporna, a string of islands belonging to Sabah. Among other things, he wanted to make an assessment of the attitude of Sabah residents who originated from Sulu towards the Philippines. These Sabah residents helped him, he said, despite the fact that the Sabah police had his picture posted as a wanted man. He concluded that, in the event of an armed conflict between Malaysia and the Philippines, a majority of the Sabah people would side with the Philippines.

The recruits traveled on one of the 50 or more fast-moving fishing boats owned by big-time smuggler Lino Bocalan. Some of his boats were painted gray, similarto the Philippine Navy fleet. They frequently traveled from Cavite to Sabah, where they loaded thousands of cases of “blue-seal” cigarettes, like Salem, Chesterfield, Union, and Champion and smuggled them to the Philippines. At that time, imported cigarettes were not allowed into the Philippines, where the local tobacco industry was tightly protected. The goodies were available in Sabah, which was, informally, a free port, a haven for smugglers.

Only 31 years old, Bocalan was already a millionaire. He kept a couple of houses on the US West Coast and was hounded by a tax evasion case in Manila. He was a much sought-after election campaign donor, and he eventual~ entered politics and ruled Cavite as governor during the martial law years (1972-1980) .Bocalan had also been among the financiers of Operation Merdeka.

In his coastal home in Cavite in 1998, Bocalan, 70, hesitates to talk about his ON participation in Operation Merdeka. Halfway through a bottle of whisky on a Sunday midmorning, he relents a bit. “Marcos told me he needed help for sabah,” Bocalan says in Filipino.”My duty was to finance the operation. I spent millions (of pesos)…I fed the Filipino trainees in Sabah, paid their salaries. I supported them. I sent my brother and my people to Tawi- Tawi and Corregidor to give food and money (to the recruits).”

A small office in the Department of National Defense (DND) had made the connection to Bocalan and arranged for his boats to ferry the agents. This was the Civil Affairs Office (CAO) headed by Maj. Martelino, and itwas the core group that planned and implemented Operation Merdeka. The CAO later distanced itself from Jabidah, claiming that Martelino had gone on leave a year before the killings. After the expose, Marcos abolished the CAO. Martelino reported to only two people: Defense Undersecretary Manuel Syquio and President Marcos. Syquio supervised Operation Merdeka while Martelino carried it out.

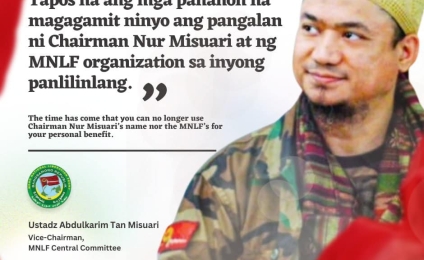

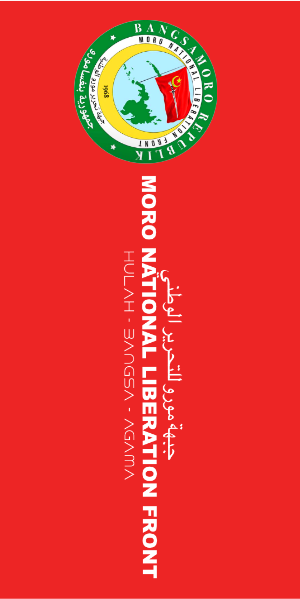

Months later, in March 1968, the killing of at least 23 trainees on Corregidor island for that mission sparked the Muslim rebellion and gave birth to the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). An officer, Lt. Eduardo Nepomuceno, was also shot dead in unclear circumstances.

A legacy of lying

Only a small group in the Armed Forces may have been involved in Operation Merdeka but it tainted the reputation of the AFF: To this day it is kept as a dark secret which many in the military refuse to talk about. Those who participated, either in the actual training or in the clean-up operations, have not fully come clean. In the end, it may have left a legacy of lying and cover-up.

In 1971, all officers and men charged in military court for the Jabidah massacre were acquitted. The major actors are by now all dead. This chapter in Philippine history will continue to have missing parts. After Jabidah, Rolando Abadilla gained notoriety as head of the Military Intelligence Security Group that arrested and killed political activists under Marcos. After his retirement, he ran and won as vice governor of llocos Norte in 1988. In 1996, after several years of surveil)ance and failed attempts, communist guerrillas shot him dead while his car was held by traffic at a busy intersection along Katipunan Avenue in Quezon City. Abad(lla’s immediate commander in Oplan Merdeka, Eduardo Batalla, had been killed much earlier in 1989, when he bungled a hostage incident

involving a bandit, Rizal Alih. Batalla, then an army general, was commander of the Southern Command.

Eduardo Martelino, the flamboyant military officer who executed Oplan Merdeka, was reported to have been imprisoned in Sabah in 1973. Martelino returned to Sabah after his acquittal to attend to “unfinished business,” his daughter Pat Martelino Lon recalls. Martelino wrote his family a letter. They believe he is dead, but a few of his former colleagues think he may still be languishing in a Malaysian prison. Martelino, some intelligence reports say, was in touch with Tun Mustapha, then chief minister of Sabah, who may have turned him over to the police. Manuel Syquio, defense undersecretary who supervised the project, has died. And lastly, Ferdinand Marcos, who knew it all, died in exile in Hawaii in 1989.

But some senior military officers and men, both retired and still in active service, talked to us to fill in the gaps of this story. A-number of them participated in the operation as leaders who gave orders or followers who implemented such orders. Others knew or were close to the people who were recruited to Jabidah,

Spying on Sabah

As it was a special government operation, details of Oplan Merdeka were known to only a few people. But the general concept was explained to the officers who were involved in it. The Philippines was to train a special commando unit-named Jabidah-that would create havoc in Sabah. The situation would force the Philippine government to either take full control of the island or the residents would by themselves decide to secede from Malaysia. Many Filipinos from Sulu, Tawi- Tawi, and parts of Mindanao had migrated to Sabah. Oplan Merdeka was banking on this large community to turn the tide in favor of secession and ultimately join up with the Philippines.

The project did not exactly start from ground zero. Even before Martelino sent his men to Sabah, Philippine Armed Forces intelligence was already eavesdropping on the island. The National Intelligence Coordinating Agency (NICA) had an agent in Sabah, watching any move to form a Muslim fundamentalist group that would expand to the rest of Borneo as well as Mindanao. In the early 1960s, there was concern over the possibility that a Pan-Islamic movement financed by Libya’s Muammar Qaddafi would reach the Southern Philippines, where a Muslim minority lived.

Rafael lleto, deputy chief of the NICA, had just attended an intelligence training course in Israel in 1963. He arrived with new communications technology, including a sophisticated transmitter. He wanted to find out what was going on in Sabah and, at the same time, to tryout the new gadgets. He sent a Scout Ranger officer, Capt.Solperino Titong, who was skilled in communications. “The mission was purely information-gathering,” Ileto says. “Titong was to ingratiate himselfwith the (Sabah) government and be in a position where he’d be trusted.” Titong ended up as close as anyone could get to the most powerful man in Sabah: he became the driver of Tun Mustapha, chief minister of the state.

A year later, Ileto left the NICA for a new appointment as commander of a PC zone covering 19 provinces North of Manila, including the area where the Huks thrived. But Titong stayed on in Sabah. ln 1967, Martelino’s CAO learned of Titong and tapped him to lead the team of infiltrators, this time for Oplan Merdeka.

Malaysia seemed an easy and vulnerable target at that time. The Federation was new and still fragile, having come into being only in 1963. It had barely taken off when Singapore, a member of the Federation of Malaya, decided to break away in 1965. Malaysia was engaged in a border dispute with its giant neighbor, Indonesia. Manila wanted to pursue its claim to Sabah at the World Court in the Hague and any discontent in the territory might have encouraged the Philippines to abandon diplomatic channels for more direct methods. True enough, Marcos cast his covetous eyes on a country that was still on its way to political cohesion.

On the ground, though, trade relations between Mindanao and Sabah picked up. Traders made regular clandestine visits and their business was classified as “smuggling.” This phenomenon used to be open and untrammelled. lt dates back to about 500 years ago, when maritime commerce thrived between Sulu and Borneo, the Moluccas, Celebes, and China. It was a glorious era. But the brisk business was not to continue. Western colonizers carved up the region and drew boundaries that blocked travel and trade. Exchanges became illicit and this peaked in the 1960s, prospering to the extent that it attracted the interest of the likes of Bocalan.

Merdeka takes off

Feeling the need to reduce smuggling in that zone, the Anti-Smuggling Action Center headed by Gen. Pelayo Cruz began looking for a special operations officer. A young captain, Cirilo Oropesa, was picked for the job. Oropesa had entered the Army in 1962 and had undertaken ranger and infantry courses at Fort Benning and Fort Bragg in the US. He was asked to submit a project proposal that was to be approved by Malacanang. Somehow, the plan landed on Martelino’s lap.

In November 1967, Oropesa received an order designating him training director and directing him to organize a provisional Special Forces training unit directly under the headquarters of the Philippine Army. Its aim was to qualify the recruits for unconventional warfare.

“It involved sensitive operations, including the cutting of commerce between Sabah and the Philippines,” Oropesa recalls. “He (Martelino) got hold of my proposal, started recruiting people, and probably realized he couldn’t do it without me.” Oropesa became operations officer of Oplan Merdeka. Oropesa’s executive officer was Capt. Teodoro Facelo. Lt. Eduardo Batalla served as personnel officer, while Lt. Rolando Abadilla took charge of supplies.

Oropesa’s training program included mountaineering, survival techniques, and the use of sophisticated communications equipment, weapons, and explosives in their camp in Simunul, Tawi- Tawi. The men conducted make-believe patrols, raids, ambushes, and infiltration behind enemy lines. But they specialized in demolition and sabotage, including incendiarism and field communication.

It became clear to Oropesa only later, in the midst of their training in Tawi- Tawi, that Martelino had his sights on taking Sabah.

All three factors converged and became the context as well as backdrop for Oplan Merdeka: the fear of a Pan-Islamic movement creeping into Mindanao, a vulnerable Federation of Malaysia, and an anti-smuggling operation. All these played into the high-adventure scheme of taking over Sabah.

From Simunul to Corregidor

The training of recruits from Sulu and Tawi- Tawi was done in Simunul, a picturesque isiand-town of Tawi- Tawi. One of Tawi- Tawi’s 300 islands, Simunul is a landmark in Philippine history, being home to the first mosque in the Philippines, built in the 14th century. It is also a breath away from Semporna, an island of Sabah. On clear nights, Simunul resjdents can see the lights of Semporna.

From August to December 1967, Martelino, assisted by Batalla, set up camp and trained close to 200 men- Tausugs and Sama aged 18 to about 30, A number of them had had experience in smuggling and sailing the kumpit a wooden boat commonly used in the area. What enticed the young men to Martelino’s escapade was the promise of being part of an elite unit in the Armed Forces. It was not just any ordinary job. It gave them a legitimate reason to carry guns-carbines and Thompson submachineguns. It gave them a sense of power.

Camp Sophia, named after Martelino’s second wife, a young, naive, and pretty Muslim, was inside a coconut plantation, fenced by barbed wire. A hut housed a powerful transreceiver and served as a radio room. Bunks were made of ipil- ipil and makeshift twigs. A watchtower stood tall in the perimeter, facing the sea. It was a world of their own making, with the trainees wearing distinct badges showing crossbones and a black skull with a drip of blood on the forehead. Their rings were engraved with skull and crossbones.

Camp Sophia became the talk of the town. Congressman Salih Ututalum of Sulu had heard about it and paid the camp a visit in October 1967. Martelino briefed him and convincingly talked about the noble “civic action” of the trainees. “I addressed the trainees, encouraging them to do well. I urged them to behave properly and to keep faith with the government,” Ututalum recalled in his speech in Congress in March 1968. “I was inclined to give Martelino the benefit of the doubt. I accepted his explanation.” He left Simunul somewhat appeased and a bit impressed by the well-equipped camp and the training officers he met who had overseas experience, primarily in Korea and Vietnam.

Ernesto Sambas, now 48 years old, was the first Simunul recruit to be commissioned officer with the rank of second lieutenant. He remembers that day in 1967 when he saw Martelino’s recruits jogging on the rugged streets of Simunul:”They looked like they were having fun.” One morning, Martelino passed by Sambas’s house, looking for the latter’s father who was then a municipal official. Martelino ended up talking with Sambas who signified his interest in joining the troops he saw.

By that time, Martelino had become famous in Simunul. The residents adored him. He was a good-Iooking, generous, and charming officer and gentleman. He had also converted to the Muslim faith and called himself Abdul Latif. People knew him to be close to the Marcos family, proof of which was his ability to convince the President to visit Simunul in 1967. He married a young lass from Simunul, 17-year-old Sophia Mirkusin, after whom he later named the training camp.

It didn’t take much on Martelino’s part to lure Sambas into joining the Sabah mission. Sambas claimed they were told early on about this plan even while they were still in the training camp in Simunul. He was thrilled by the prospect of becoming a soldier and joining an elite mission at that. In August 1967, Sambas joined Martelino’s men in their combat training at Camp Sophia, which overlooked the sea.

Today, no trace remains of a military camp in Simunul, not a single marker. What was once Camp Sophia now looks deserted, planted to palm and coconut trees and wild grass, with empty packs of kretek cigarettes lying on the ground. But the lady after whom the camp was named still lives in Simunul with her husband and two children. Now 49 years old, Sophia is known by neighbors and friends as Sophia Lazarato, a teacher who married a fellow teacher in 1974 or six years after the event that turned her first husband, Martelino, into a controversial national figure.

New Year at sea

It was a forced marriage, Sophia recalled in an interview in June 1998. She was very young then, while Martelino was Mindanao’s most famous soldier and a veritable lady’s man. Sophia did not like him when they first met at a celebration of Martelino’s conversion into Islam. The soldier was smitten and used his power with the local executives in Simunul to convince Sophia’s sister to agree to the marriage. They got married in October 1967, after only their second meeting. Three cows were served; Martelino gave a dowry of P5,000 plus high-powered firearms to Sophia’s family. Sophia’s only remembrance of Martelino now is a compilation of magazine and newspaper articles about him.

On December 30, 1967, anywhere from 135 (Aquino’s count) to 180 (Oropesa’s count) recruits boarded a Philippine Navy vessel in Simunul bound for Corregidor. For two days and one night, the troops sailed from the outhernmost tip of the Philippines to Corregidor. They spent the New Year at sea and reached the island off Cavite on January 3, 1968.

Corregidor was the last bastion of Filipino-American resistance against invading Japanese forces. It was the site of many deaths and some describe its history as written in blood. Today, it is a tourist destination, with the ruins ofbattle well preserved. However, Jabidah is never mentioned as part of Corregidor’s storied past. The hospital turned military barracks and the airstrip where the killings took place are not included on the routine tour. But graffiti of trainees’ and trainors’ names, places (“all from Sulu,” “Siasi market site,” “Tapul, Sulu’), and one memorable date-“Jan. 3/68,” when they arrived in Corregidor-bear witness to Corregidor’s connection to another island.

Corregidor was also the site of other military training courses. Oropesa told Congressional committees that he trained Fillipino Scout Rangers and Special Forces, as well as foreign allies, like Vietnamese and Laotian officers.

Before the recruits docked in Corregidor, Defense Undersecretary Syquio and Gen. Espino, Army commander, inspected the campsite. The old Corregidor hospital was cordoned off and declared a restricted area. It was to be the military barracks. The trainees were to stay inside the bombed-out hospital on the topside of the island, the highest point on Corregidor, surrounded by trees and bushes.

Once on the island, the trainees were ordered to cut the trees surrounding the camp. They were taught to dig foxholes and use parachutes. They kept a rigid schedule, and were up at 5 o’clock in the morning for a two-hour jog followed by drills. Lectures took place in the afternoons.

The Corregidor training sent Martelino away from his young wife who lived in Sirmunul. But Sophia never asked what Corregidor was all about. When the Jabidah massacre was exposed, she did not know a thing and she never saw her husband again. “He did not even bother to write. The trainees in Camp Sophia told me he had another woman.”

Sambas recalls seeing many other soldiers on Corregidor, but their batch from Simunul was confined to one area in the island.”1 felt that they were hiding us from the rest,” Sambas says. He remembers the names of their commanders: Facelo, Abadilla, Martelino; Col. Ciriaco Reyes was in charge of finance while Nepomuceno took care of personnel. Sambas was easily liked by his commanders and he had no complaints at all.

It appears that there was discrimination against the Tausug trainees. Sambas said he got his pay but those from Sulu did not. If stereotypes are to be believed, Tausugs are known to be ferocious fighters, much disliked by the peaceloving Sama because they bring their age-old feuds and confiicts with them even if they migrate to places like Tawi- Tawi. Sambas is a Sama from Simunul.

As a commissioned officer, Sambas also noticed the growing restlessness among other Muslim youths, notably those recruited from Sulu. The recruits were getting impatient because they couldn’t send a single centavo back home. Their promised pay of P50 a month was never given The officers were aware of the agitation among the troops. They knew that it was just a matter of time before a mutiny erupted. As a precautionary measure, Abadilla and the rest took shifts guarding their own barracks at night. Sambas remembers that they sent at least 16 of the Muslims back to Sulu because they were always complaining. He saw them board a naval patrol boat.

An invasion turns mutinous

Jibin Arula, from Sulu, and a survivor of the bungled training, shares this account of the Corregidor training 30 years later:

“We were shown maps of North Borneo. They showed us where we were going: Kota Kinabalu (Sabah’s capital). We were going to be issued passports so we could go to town legally and organize Filipinos, our relatives and friends. Three hundred of us trainees were to be divided among the three provinces of North Borneo. ‘lf war comes, with whom shall you side?’ We were supposed to ask them that. If they said that they’d side with the Philippines, we would take them to the mountains of KK and give them arms. We would demolish their communications equipment, burn them, plant dynamite, and simultaneously explode them. These would cause a blackout. Then we could rob banks, we were told, and kill Malaysian police. We’d just start it (trouble) and go home. We would need to look for a boat to take us back. We’d grab any boat… It would be war.”

Oropesa, when questioned in Congress, admitted that one of the subjects taught at Corregidor was the invasion of Sabah. “I wish to honestly say that I have a feeling that this training… is purposely for infiltrating Sabah,” Oropesa said at a Congressional hearing. But he backtracked and clarified that “any land or country or portions of a country mentioned is only taken as a reference for instruction.”

By the fourth week of February, some of the trainees started to get restless. Since their arrival in Corregidor, they had not been paid a single centavo. They were promised a monthly pay of P50. Their food was miserable. Every day, they ate tuyo (dried fish) with burnt rice. They slept on ipil wood and cots. They were lonely and isolated. Meanwhile, their key officers pampered themselves in comfortable, airconditioned rooms at the Bayview Hotel, across the Manila Bay, a short boat trip from Corregidor.

.The trainees decided to complain and secretly wrote a petition addressed to President Marcos, signed by about 62 trainees. Others placed their thumbmarks. They wanted their pay plus an improvement in their living conditions. The letter was given to a Tausug from the Philippine Navy. Somehow, it reached Martelino.

Martelino visited the trainees and assured them of their pay. Then, in a separate visit on the first week of March, he called the four leaders of the petitioning group. Martelino told a Congressional committee: “I sent for the four trainees-Lt. Batalla fetched them-and spent about one hour talking to them (about their complaints) at the bottomside of the island. After talking to them, I sent them back to camp.”

But these four men never returned to camp. Arula recalls they were told they were returning home. Apparently, they were brought to Manila. Martelino said they deserted. Dugasan Ahid, one of the four leaders, later testified in Congress that his three companions were shot by their trainors, including Martellno. But, upon cross-examination, Ahid wavered. News reports said he “began to falter and contradict himself. He admitted that he didn’t see the officers shoot his companions.” The three, to this day, remain unaccounted for.

Gen. Segundo Velasco, AFP chief of staff; later said that Ahid surrendered to defense officials on March 22. Ahid said he escaped along with three others in a pumpboat from the Corregidor landing. After reaching Bataan, he and his companions took separate ways.

After Ahid and company left, the trainees were given fiesta food: goat, beef, and Nescafe coffee with milk. Almost every night, there was music and dancing. A few women were there. They also had an amateur singing contest. Arula recalls belting out Sayonara. But with the good food and entertainment came the bad news: the rest of the signatories to the petition were disarmed. Effective March 1, all 58 of them were considered resigned.

Some 60 to 70 trainees, meanwhile, were transferred to Camp Capinpin in the jungles of Tanay, Rizal, on the first week of March. Gen. Espino testified in Congress that the group was moving to an “advanced phase of training… and they envisioned an exercise… all the way to the Pacific Ocean. “These men, the Army commander said, were a cut above the rest so they were chosen forthe more rigorous training in Tanay. They were not signatories to the petition.

On March 16, another batch was taken away from Corregidor. About 24 recruits were told that a Philippine Navy boat was docking early that morning to ferry them back to Sulu. Espino said that, in addition, two were returned home by Air Force plane. This group, Espino said, “could not stand the rigors of training” and thus were sent home. But Sen. Aquino, who investigated the case, refuted this, citing some of the trainees’ letters to their families which he obtained while on a visit to Sulu and Tawi- Tawi. Generally, the letters showed they were proud of their achievements, having survived in tough conditions and having climbed the highest mountain on Corregidor.

These 24 men gathered their personal belongings and shortly before dawn they were brought to the island pier. They boarded the same boat that had brought them to Corregidor in the New Year. Aquino met this batch of 24 in Jolo when he did his own sleuthing in late March, after the story of Arula broke out in the press. William Patarasa, 18, one of the trainee-petitioners, corroborated all the points raised by Arula, Aquino said in his Senate speech.

Then, on March 18, another 12 recruits were told to prepare for home. At 2 a.m., they left camp. These men, till today, are unaccounted for. Soon after, on the same day, another batch of 12 was told that they were going to leave at 4 a.m. Why a dozen per batch? Because the plane, they were told, could carry only 12 passengers. Arula belonged to this second batch.

A survivor’s testimony

Arula’s memory of this day remains vivid: “Lts. Nepomuceno and Batalla were the ones who picked up the two batches. They said we were going for R & R.

We went to the airport on a weapons carrier truck, accompanied by 13 (non- Muslim) trainees who were armed with M-16 and carbines. When we reached the airport, our escorts alighted ahead of us. Then Nepomuceno ordered us to get down from the truck and line up. As we put down our bags, I heard a series of shots. Like dominoes, my colleagues fell. I got scared. I ran and was shot at, in my left thigh. I didn’t know that I was running towards a mountain. When I reached the mountain, I clung to an ipil-ipil, my palm skin peeled off, and I rolled off the steep rocky mountain. I closed my eyes. I temporarily lost consciousness but when I regained it, I was lying on the shore and I heard shots. Sand was bursting from the shots, as if bullets were chasing me. I swam and I got a plank of wood as my lifesaver. I heard the roar of a truck and two pumpboats. By 8 a.m., I was rescued by two fishermen on Caballo island, near Cavite.”

Later, in a Congressional hearing, the training officers gave their versions of what transpired. One of them was Capt. Alberto Soteco, a medical doctor and graduate of the Special Forces Course (Airborne) of the Philippine Army. He said that on March 18, 3:30 a.m., he was on board the weapons carrier with Nepomuceno, who was at the wheel. With them were seven trainees, armed and in civilian attire, and three cadre personnel. (This account, however, contradicts Arula’s story who said that they had been disarmed after they filed their complaint.) They stopped at Kindley airstrip which was almost surrounded, at the back and both sides, by thick ipil-ipil trees. The front was clear and the rest, from the shed westwards, was all ipil-ipil. They were supposed to do night air infiltration exercises, mark the airfield for landing of other troops, do simultaneous paradrops of personnel and supplies, and provide security around the airfield. But the trainees started to run towards the airport shed, about 25 to 30 meters away. Nepomuceno fired a warning shot.

“He (Nepomuceno) requested me to help him search for trainees,” Soteco told a Congressional committee. “After a few minutes, Nepomuceno found out that only M/Sgt. Munar, myself and (Angel) de la Cruz were with him. We continued the search but because it was too dark, we feared being ambushed. Nepomuceno decided to return to base camp. We arrived at 5:45 a.m.”

For his part, trainor Angel De la Cruz, in his testimony, merely said that the trainees refused to obey the orders of Nepomuceno for the exercise.

For many of the soldiers involved in Oplan Merdeka, there was nothing wrong with a plot to take back territory that they believed the Philippines owned. It was the patriotic thing to do. Looking back, they say that if not for the bungled training, the killings would not have ensued and Oplan Merdeka would have pushed through. lt was a legitimate project with a worthy goal.

An officer is murdered

But the killings of trainees were not the end of the mayhem. On March 19, Lt. Nepomuceno was killed on Corregidor. Nepomuceno, a PMA graduate, was a Metrocom officer until February 1, 1968, when the Secretary of National Defense issued a special order assigning him to the Special Forces training on Corregidor. The trainees had already been there for a month when Nepomuceno arrived.

From within the Constabulary, Batalla recruited Abadilla and Nepomuceno into the special mission. Abadilla and Nepomuceno were PMA classmates, inseparable since their cadet days. While Abadilla was assigned to monitor the daily training of the recruits, Nepomuceno took care of the logistics and personnel supervision. There were to be two battalions of trainees for the infiltration and invasion.

Retired general Dictador Alqueza remembers those days because he was actually about to replace Nepomuceno as the logistics officer of Oplan Merdeka when the latter was killed. He had already sought permission from his father, telling him that he was going for one year’s schooling in Malaysia. Alqueza remembered that that was what Batalla and Martelino told him, that the operation would last a year. In any case, Alqueza was all set to replace Nepomuceno, because, Alqueza said, “I got the impression that there were complaints against Nepo.” (Nepo is the nickname of Nepomuceno.)

But a retired general who knew Nepomuceno, Romeo Padiernos, said he doubted if Nepomuceno had a hand in the abuse against the trainees. He believed that if Nepomuceno was killed at all it had to have been because he was fighting for the right of the trainees to be paid on time. “He was a very idealistic young man,” Padiernos recalls. “I can’t imagine Nepo abusing others… I can actually picture him taking the cudgels for the trainees and speaking on their behalf. Maybe somebody decided to silence him.”

Abadilla was pestered by his PMA classmates no end about who really killed Nepomuceno. Padiernos himself confronted Abadjlla about it, but the latter would not talk about his classmate’s death. Abadilla never discussed the details of Oplan Merdeka or of Nepomuceno’s death with any of his classmates, a silence that angered some of them.

Nepomuceno was shot in the forehead and the bullet came out somewhere in the nape. The line of trajectory indicated he must have been kneeling when he was shot. According to Sen. Aquino, the Army wanted to bury Nepomuceno without an autopsy. He gathered this information from Nepomuceno’s parents. Lawyers from the Civil Liberties Union handled this case but no charges were filed.

The official story was that Nepomuceno, the commanding officer of the training camp, discovered the plot to liquidate the officers. On March 19, when Nepomuceno was taking the trainees to a bivouac area to disarm them, he was suddenly abducted by Alfonso Mamaroglo, a trainee from Camp Aquino, Tarlac, and supposedly one of the leaders of the mutiny. He ran amok and shot Nepomuceno in the face. This resulted in a gun battle. Another trainee, Tagumpay de la Cruz, a former Huk, was killed with Mamaroglo. One of the assistant trainors, Capt. Rosauro Novesteras, also from Tarlac, was wounded, shot by Mamaroglo. AWilfredo Pahayahay was also wounded.

Various versions, with slight variations from the official story of Nepomuceno’s killing, emerged during the Congressional hearings. Oropesa, in his testimony, said that a “team was out on a tactical exercise” on March 1.8, between 3:30 and 4 a.m. While the instructor was trying to form the group in preparation for the exercise, somebody shouted “Magdagan na kita. ” (Let’s run, let’s go.) The group ran and Lt. Nepomuceno, the instructor; commanded them to stop. He fired a shot in the air after which he gave chase to the fleeing trainees. In the process, there were several shots heard. It was very dark.

After the chase, Nepomuceno came upon only one trainee, De la Cruz, who accounted for firing several shots. None of the other members of the group could be located so they went back to camp. After breakfast, Nepomuceno organized a search party. The search took the whole day but no one was found. On March 19, another search was conducted. Shots were heard. Nepomuceno was found dead and an assistant trainor, Novesteras, was wounded.

Trapping a trainee

An eyewitness account by Manila Times reporter Cesario del Rosario who was on Corregidor on March 20, 1968, contradicts the official story about the death of Mamaroglo, the suspect in Nepomuceno’s murder. Mamaroglo was shot on March 20, and not on the 19th, as the generals claimed. Del Rosario wrote: “A uniformed man carrying a rifle crouching and running towards the hut was shouting, ‘Sumuko ka na…’ A voice replied, ‘Huwag na ninyo akong hulihin. Uuwi na ako sa Tarlac.’ Before the soldier could reach the hut, a bullet hit his face and I saw him fall downward. He was identified as Tagumpay de La Cruz of Tarlac. We were told later that he was asked by his comrades to convince Mamaroglo to surrender as they were townmates. The firing continued. About 3:15 p.m., Mamaroglo came out of the hutwith raised hands apparently to give up but successive shots rang out and he fell dead.”

The various testimonies also revealed more of the nature of the commando group. It turned out that a number of men from Tarlac, part of a paramilitary group, were with the core of the Jabidah forces. Most, if not all of them, were members of the Civilian Commando Unit (CCU), the precursor of the civilian Home Defense Forces. The CCU, says Eugenio Alcantara, who was on Corregidor as a 31-year-old training assistant, was an anti-Huk group. “We were informers,” says Alcantara of his work as team leader at the CCU. He was used as an asset by the AFP j-2 or intelligence unit. “They chose us (for Jabidah) because we were pro-Marcos, faithful to the government. Our order was to help in training (recruits) .” De la Cruz, for his part, operated in Nueva Ecija in 1950. He was employed by President Magsaysay in the Department of National Defense to help in the anti-dissident campaign in Central Luzon. Subsequently, he worked as an agent for the DND.

While questions remained about who really killed Nepomuceno, it was certainly Batalla, the immediate superior of Nepomuceno in the camp, who was responsible for Mamaroglo’s death. Sambas, one of the recruits from Tawi- Tawi, witnessed the shooting. He was still on Corregidor when the situation turned for the worse. He was told by his commanders that Nepomuceno had been killed by one of the trainees, Mamaroglo.

Shocked and pained by the incident, Capt. Batalla launched a search for Mamaroglo who had by that time gone into hiding in the jungles of the island. Sambas tagged along and, early in the morning after long hours of search, he saw Mamaroglo trapped in a makeshift hut. Mamaroglo refused to surrender, prompting Batalla and his men to shoot at the hut. When he came out, he was all bloodied but still alive. Batalla shot him right there and then.

Batalla never denied to his colleagues that he shot Mamaroglo. The way he shot the fugitive-the bullet entered Mamaroglo’s forehead, right above the nose-was the talk among the PMAers who were at Nepomuceno’s wake. Sambas saw nothing wrong with the killing just as he saw nothing wrong in joining a mission to invade Sabah. To him, the idea was a noble one. After the expose on Jabidah, he was among the many court-martialed by the military in a mock trial. He was later transferred to Nueva Ecija but was not given any combat post again.

The cover-up

It was hard to get to the bottom of Oplan Merdeka. All CAO reports on the project were burned on orders of Martelino. Documents were tampered.

Reports were falsified. In Congress, the officers gave uncoordinated testimonies and bungled accounts, especially about the missing trainees and the killing of Nepomuceno. Basic documents containing the names of all trainees were unavailable.

Oropesa and an enlisted man, M/Sgt. Cesar Calinawagan, were later charged before the military court with “feloniously” preparing morning reports of the Special Forces Training Unit. They made it appear that the morning reports for the months of November and December 1967 were faithful to the dates. Actually, they were prepared only in the latter part of December 1967 in Fort Bonifacio. For the month of November, which has only 30 days, 31 reports had been made. This little error gave the officers away. Facelo was also partly responsible for this oversight.

Oropesa, Facelo, and Abadilla were likewise charged with falsifying the signatures of eight trainees. They made it appear that these persons signed the payrolls of the Special Forces Training Unit for the months of January to March 1968. However, these trainees never received their salaries nor signed the payrolls.

In Malacafiang, President Marcos denied outright the opposition’s accusation that Project Merdeka was a sinister plot to invade Sabah. He ordered the Armed Forces top brass to investigate the incident. The orders were sent to Gen. Segundo Velasco, AFP chief of staff; Brig. Gen. Espino, the Army commanding general; and Maj. Gen. Manuel Yan, the Constabulary chief and concurrent vice chief of staff.

In their report, the generals said the training was part of the “counterinsurgency” program being conducted by the government and that the killings were caused by “simple munity and desertion by trainees who had been kept under sustained, simulated, adverse, and severe jungle conditions.” They surmised that the trainees must have broken down under pressure from Nepomuceno, their commanding officer, who, in the words of the generals, was a “hard disciplinarian.”

The AFP leadership chose not to dignify the reports about the Sabah invasion. It wove a tale that heightened the communist threat: “Information from friendly neighboring countries emphasizes the fact that communist agents were operating in the general area of our southern backdoor and indicates an upsurge in communist activities there. Additional intelligence information indicates the communist agents have infiltrated through our southern backdoor.” Hence, the generals told the public, the decision to organize “well- trained counterinsurgency forces” such as the one on Corregidor island.

Gen. Espino told Congress the Army was “never involved” in Project Merdeka. He said that his office received two directives: one in September 1967 for I/special forces training,” and another in November in the form of a radio message from the AFP chief of staff “to conduct not later than the first week of January training on unconventional warfare for counterinsurgency.” He also admitted flying to Corregidor twice, before March, to inspect the unit. Upon deplaning from his 8-17, Espino was given planeside honors and he was quite impressed by the trainees’ appearance. On his second visit, he saw the trainees engaged in grenade throwing and rappeling.

Espino refused to talk about Operation Merdeka in an interview. “The less we talk about it, the better,” he told us.

One story, two versions

The official story came in two conflicting versions. After the generals came up with the “counterinsurgency” account, Martelino, “case officer” of the clandestine project, regaled congressmen with a fantastic scheme of deception. The real intention behind the rather unorthodox training of mostly Tausug men, he revealed in Congressional hearings, was to stop the plans of private armies to invade Sabah. These men, he said, were actually members of armed groups in Sulu out to infiltrate Sabah and grab it. The men were made to believe that they were going to invade Sabah-but, actually, their training was just a cover to keep them under control.

In military parlance,” Martelino told Congressional committees, “the mission was that of denial, to deny these people from pursuing their objective.” Precisely, Project Merdeka was, in fact, organized to try to dissuade these groups from pursuing their plan. “The reason for this was that any attempt at invasion of Sabah by Filipinos would embarrass the government and create an international crisis for our government, ” the flamboyant Martelino said with a straight face. Effortlessly, he turned around the facts. Martelino referred to intelligence reports concerning separate armed movements planning to launch an invasion of Sabah. They were emboldened by the Philippines’ pending claim to Sabah, Martelino said, so that they began to take their own steps.

According to him, Oplan Merdeka had two phases as a mission of denial. The first was in Simunul, from August to December 1967. The second phase

involved training on Corregidor. The project was approved by the AFP chief of staff and commander in chief and intelligence funds were used.

While a military court was trying the case, Martelino and other officers were undertechnical arrest, confined to restricted areas in Fort Bonifacio and Camp Capinpin in Tanay. But Martelino was a special case. Often, he had important guests. “My dad played poker with Marcos and Abadilla in Fort Bonifacio at night while under house arrest in a heavily guarded house, with grills,” Pat Martelino Lon says.

Martelino had been obsessed with Malaysia since the 1950s. In 1959, he wrote a book about it, published in New York, where he was then serving as press attache of the Philippine embassy. In Someday Malaysia, Martelino longed for the fulfillment of a dream of the late Philippine President Manuel Quezon: the integration of Burma, Thailand, Annam (now central Vietnam) , Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines into a Commonwealth of Malaysia. In Quezon’s time, onlyThailand was independent.

“The Malayans certainly have the means to collectively achieve greatness,” wrote Martelino.”Togetherthey compose one-fifth of the world’s total population. Beneath the surfaces of their lands lie vast untapped treasures of oil, gold, copper, tin, manganese, and other rich metals.”

The son of the first Filipino superintendent of the PMA, Martelino joined the PAF during the time of the late President Ramon Magsaysay. When Ferdinand Marcos became president in 1965, he was impressed with Martelino’s skills and his penchant for special operations. Martelino never hid from Marcos his stand vis-a-vis the Philippine claim to Sabah. A newspaper interview has him saying that he would often tell Marcos that the Philippine military was in a good position to seize Sabah by force if the Malaysians refused to return it to the Philippines through legal means.

A word war erupts

In Malaysia, the government raised the stakes with a display of anger and anxiety. In a strident tone, the Malaysian government lodged a formal protest with the Philippines “over the report of the existence of a Philippine special force to conduct infiltration, subversion and sabotage in Sabah.” They were taking the report “most seriously” as they had just arrested more than 20 armed Filipinos “who were unable to explain their presence in Sabah. “Tun Mustapha, chief minister of Sabah, denounced the Philippines for “Irresponsible adventurism.”

Malaysia abrogated the anti-smuggling agreement it signed in 1965 with Marcos, withdrew its embassy staff from the Philippines, and demanded that the Philippines implement its announced withdrawal of its own staff. It also ended its participation in regional meetings that involved the Philippines.

In Sabah, a sense of danger suddenly swept through the island. Emergency security measures, some quite exaggerated, were put in place “to counter threats of infiltration from the Philippines.” Young men from 18 to 28 years old had to register for military training. A vigilante and local defense corps was immediately formed “to watch illegal landings and to report suspicious activities to the military, guard key positions, and to assist police in territorial attacks.” Family members and occupants of houses in certain areas considered sensitive were asked to register. Arrivals and departures had to be strictly recorded. The state government wanted to impress on residents the urgency of the situation and enlist their help in tracking down movements of “subversive elements, would-be saboteurs, and infiltrators.”

In a tit-for-tat, Sabah police picked up Filipinos for illegal entry and seized a Philippine boat, claiming that the motor launch, which had 15 Filipino crew members on board, had intruded into Malaysian territorial waters. Not taking this lightly, Marcos ordered the deployment of more troops and Navy ships to the border area between the Philippines and Malaysia. A word war ensued in the newspapers.

The Corregidor fiasco, in a way, served as a wake-up call to Kuala Lumpur. It could no longer take its eastern “backdoor” for granted. Then Prime Minister Tungku Abdul Rahman announced plans to hasten agricultural development and increase investments in Sabah.

The Philippine government stood its ground. Calling the Malaysian protests a form of intervention in its domestic affairs, the Philippines strongly denied the charge that Jabidah was formed to invade Sabah. It also renewed its claim to Sabah. Marcos instructed Philippine Ambassador to the UN Salvador Lopez to meet with the UN Secretary General U Thant “for a Malaysian agreement to an immediate settlement of the claim to Sabah through the World Court.” A Malaysian foreign ministry spokesman said that they did not find it timely to seek recourse with the World Court, stressing that preliminary talks should first be held before any agreement was made on the mode of settlement.

Malaysia also reminded the Philippines of a UN survey in 1963 which showed that the people of Sabah wanted to be part of Malaysia. At that time, the Federation of Malaysia was being formed to include Sabah and Sarawak. The Philippines and Indonesia raised objections, prompting the U N to send a team to the two potential members of the federation to determine their sentiments. Secretary-General U Thant announced the UN findings two days before Malaysia Day, which would fall on September 16, 1963. He said that a sizeable majority of the people of Sarawak and Sabah wished to join Malaysia. Lee Kuan Yew has vivid recollections of this period in The Singapore Story: “The next day (September 15, 1963), Indonesia and the Philippines recalled their ambassadors from Kuala Lumpur and declared that they would not recognise Malaysia, and on 16 September huge crowds gathered in Jakarta for an organized display of ‘popular rage,’ then the conventional Third World protocol for diplomatic protest.”

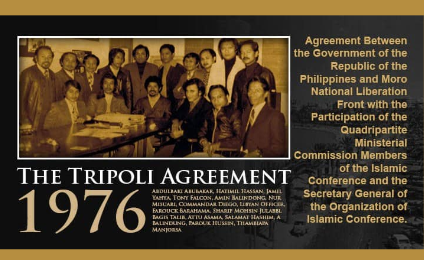

A refuge for the rebels

Years later, in 1968, relations between the Philippines and Malaysia soured, this time more intense than in 1963. Malaysia took its revenge a year after the Jabidah killings. It provided succor to rebels from the secessionist MNLF aiding them with arms and military training in Sabah. For years, Sabah was home to the MNLF. For Tun Mustapha, Sabah’s chief minister who claimed his paternal lineage from the sultans of Sulu, the issue had a religious dimension as well. Committed to Islam, he was driven by a mission to convert all residents of Sabah to Islam and to propagate the faith among non-Muslim neighbors.

The University of Malaya’s Prof. Gorpinath cites reports in 1973 that Marcos, either directly or through Indonesia, had proposed to the Malaysian government that Manila would renounce publicly its claim to Sabah if Malaysia could assure the Philippines that it would stop giving sanctuary to the MNLF.

The Philippine claim to Sabah remained a contentious issue through the Marcos years. In 1977, during the Asean summit in Kuala Lumpur, Marcos announced his intention to drop the Sabah claim-in the spirit, he said, of regional cooperation. He did not go beyond a verbal commitment, however, because politicians back home denounced his statement.

When Corazon Aquino became president in 1986, she did not revive the claim but neither did she rehabilitate relations with Malaysia. It was a dormant time for the two countries’ relations. It was only in 1993, when President Fidel Ramos made the first official visit of a Philippine head of state to Malaysia in more than 30 years, that ties between the two countries flourished. The claim to Sabah was never mentioned as Malaysians rushed to invest in the Philippines and as diplomacy and trade intensified. During the first year of President Joseph Estrada (1998-1999), the old claim to Sabah did not figure at all.

Today, 31 years later, the memories of Jabidah may have faded and the Philippines and Malaysia may have deliberately kept this sensitive and regrenable incident under wraps, the better to forget it and to keep relations placid and trouble-free. One officer involved in the cover-up operations on Corregidor calls the phenomenon “selective amnesia.” Former Executive Secretary Alejandro Melchor, who worked with Marcos before the martial law years, says that “It’s about time we put a closure to this chapter in our history.”

But can a nation close a chapter as muddled as Jabidah ?

Cross-posted from:

http://mnlfnet.com/Articles/Merdeka-Jabidah.htm

– Awarded for his role in promoting peace and dialogue in the Southern Philippines, particularly in the Mindanao conflict1_small.png)